Digging up our first meteorite (yet to be officially named*) was a massive team effort and a huge relief. It’s also been a news sensation and you can read about it on WA Today, SBS News, The Washington Post, Time Magazine and most everywhere you look on the internet today**. The search story is breathtaking, and the awesome teamwork and science that has led to this moment even better. Here’s a breakdown of what it is and how it really happened:

The rock:

- 1.6 kg of rock, lumpy with a black matte-finish fusion crust (burnt and melted layer) which is common for meteorites

- Is most likely an ordinary chondrite, though is yet to be geochemically confirmed

- Smells a bit like salty mud!

- It’s a meteorite, which means it’s a fragment from the solar system, likely to have been in existence in it’s current state since the beginning, which makes it about 4.5 billion years old

- Wondering why no one is wearing gloves? This rock is as Earth-contaminated as you can get, having rested for more than a month in thick mud. Handling? Not an issue.

The fireball:

- Blazed through the skies around 9:15 pm on November 27th, 2015

- Predicted to be 80 kg when first entering the atmosphere, travelling at about 50,000km/hr

- Locals and five of our Desert Fireball Network (DFN) cameras saw it’s greenish burn for about about 6 seconds

- It stopped burning around 18 km above the Earth’s surface, and fell at a pretty steep angle down to the middle of Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre South in the state of South Australia

The search:

- Our cameras capture the whole sky every night, but we soon realised this fireball was our best chance yet at recovering a freshly fallen meteorite – the triangulation and modelling team got on to it straight away

- Team 1: Martin Cupak and Ben Hartig head out to South Australia to do a flyover, capturing this crater-like impact in the lake

- Permissions sought, plans made for the ground search, to be done straight after Christmas by Team 2: Phil Bland, Jonathan Paxman, Robert Howie

- Meanwhile, Team 3 back in the office continue to work on the data to calculate the most accurate search area (Team 3: Martin Towner, Martin Cupak, Ellie Sansom, Hadrien Devillepoix)

- Team 2 is joined by Dave Strangways and Dean Stuart from the local area. They’re Arabana men, traditional custodians of the lake

- By the end of day 2, the team are getting quite despondent – the rains are coming and not only will that mean certain bogging of the quad bikes, the impact feature will be washed away

- On day 3 the services of Trevor Wright, local tour flight operator are requested and the air and ground teams working together finally find the somewhat washed away dent in the lake

- After some agonising minutes of digging, first with shovel then by hand, Phil pulls out the meteorite, covered in clay-like mud***

What it means:

- When a meteorite is seen falling and then recovered, that’s pretty rare. When it’s captured on a camera network too, that’s gold – the orbit (and asteroid parents) can also be determined, providing a much better understanding of the solar system’s foundations

- Phil has found meteorites before using a camera network – Bunburra Rockhole and Mason Gully are both Australian desert meteorites

- BUT they were proof of concept finds for a much bigger digital and autonomous network which the team has spent the last three years building

- Finding our first meteorite means we can refine our modelling tools and start the search for many more already on our database, and yet to fall through the sky!

*The meteorite will only have an official name after classification and acceptance by the international Nomenclature committee of the Meteoritical Society. We’ve asked the local indigenous mob, the Arabana people to give it a local area name

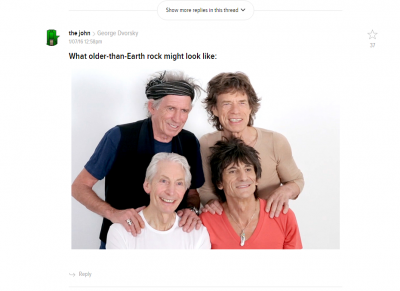

**We’ve particularly enjoyed the comments on Gizmodo including this one:

***You’ll hear on the video that Phil originally thinks it’s an iron meteorite. It’s not. Once the awed excitement died down, and he realised how injured his digging hand was, it felt a lot lighter!

Want to know even more?

Ask a question on Facebook or Twitter or read the official Curtin University release.